Evil, Decency, and Fear

An Inclusive Interdisciplinary Conference

Saturday 9th March 2019 – Sunday 10th March 2019

Prague, Czech Republic

ABSTRACT AND PAPERS

Narratives of fear: women and fear as entertainment

Moy McCrory

University of Derby, United Kingdom

We are drawn to that which we don’t know. But is fear really the unknown, when so many women experience fear daily living in hostile societies when we fear to walk down certain streets, get into an unmarked taxi, wait alone on unlit stations and find we are the sole person on the tube, when a man appears?

This is the reality of women’s experience. And we know what we fear. We fear the random act of violence generated towards all women simply because we are women.

But what we don’t know is something subtler. The unknown for women does not lay in cliché ridden images of being stalked, or followed or the strange thing behind our shoulder (usually a man). We know this. We dread it. But as authors and readers we also dread its predictability; yet again so many horror writers use the trope of the female fleeing something, or we see a woman walking faster (always in high heels which click clack and announce us to our attacker).

This paper and reading attempts to posit a different level of fear by looking at women scaring women. This takes a different route beyond the use of greater strength or physical menace (though there will be menace, it is mental, rather than practical). Looking at the nature of curses, of hauntings and of visitations as elements with which women can scare women, this paper will set the female protagonist loose in an attempt to reposition the contemporary ghost in the framework of gothic fiction. I will also give an account of hauntings in my past and current creative work with a short reading from these.

Examining the Concepts of Dossierveillance and Psuchegraphy in the Context of Communist Romania

Cristina Plamadeala

EHESS, Paris

-no abstract available-

Philosophy of Decency

Nicole Note

Educational Sciences and Center Leo Apostel for interdisciplinary Studies

In the announcement of the conference, decency is considered a phenomenon, even a difficult and confusing one. This paper attempts to achieve a deeper understanding of it, drawing on (trans)phenomenological analysis. Next to defining decency in a narrow sense as conformity to moral standards, a virtue or an acquired characteristic, it assumes that awareness can be enhanced if decency is also considered as an act. Decency is not, it is enacted in the lived experience of being confronted with the other’s inherent human dignity. Philosophically, we can articulate this as being exposed to the very experience of an ontological freedom to which we are ontologically* committed, despite our actual acting.

Analysis of mediation processes can shed light on such abstract formulations. In mediation, parties are typically engaged in a conflict, focusing entirely on reproaching each other, with any mutual connection being absent. The mediator’s task is to bring parties back to their own dignity and make them express their needs, rather than their grieves. Expressing their needs, and subsequently listening to those of the other party, leads to a change in perspective, but also in the quality of the relation: the other can become ‘human’ again. Despite oneself, a connection with the other is reinstated. Only then can practical arrangements really have a long-lasting effect.

This opening towards the other can be given many names, yet essentially it is the enactment of decency, a recognition of the other as a genuine other being, regardless of the mutual differences of opinion. The subtle distinction this paper wishes to establish is that decency is not fixed or tied to a person’s character; we all renew in an embodied way our awareness of decency and indecency in encounters where people’s dignity is valued or not, also as a third party watching (in)decency.

Decency and Empathy: The Perspective of Interdisciplinarity – from Phenomenological Hermeneutics to the Academic Library

Ineta Kivle

Key Words:

decency, tolerance, empathy, library, phenomenology, hermeneutics, interdisciplinarity

The study views how philosophical cognitions of phenomenology and hermeneutics are applicable to interdisciplinarity of academic library. In this case philosophical concepts are explored: Empathy of Husserl`s phenomenology; the principle “Let things be” of Heidegger`s fundamental ontology; Bildung and Dialogue of Gadamer`s hermeneutics. Husserl`s phenomenology acknowledges empathic attention to things and ideas as well as to different theoretical and practical experiences. In Heidegger`s philosophy empathy is developed into the structure of Being-in-the-World (In-der-Welt-Sein) – listening to being, letting the thing be as it is. Gadamer`s views on Bildung and Dialogue give perspective to understand interdisciplinarity as decent attention to each other and respectful attention to different traditions. On the bases of these philosophical cognitions it is shown how decency and empathy influence interdisciplinary research from practical point of view. Uniting philosophical concepts with practice of institutions of cultural memory and analysing functions of academic library in multidimensional perspective show new references for library beyond its traditional activities.

In this case, the current study:

- exploring phenomenological and hermeneutical cognitions shows possible model of development of historical academic libraries;

- respects library as cultural and educational institution;

- emphasizes mutual understanding, empathy, and tolerance of different experiences and cultural horizons;

- views innovative research and possible models of collaboration among personalities, library`s collections and academic departments;

- develops a particular way of interdisciplinarity, uniting technological solutions with innovative creative attention to cultural heritage and memory studies.

poliTE – Social Appropriateness for Artificial Assistants – A project researching the nature and genesis of decency

Jacqueline Bellon

Key Words:

social appropriateness, social conduct, decency, socially aware technology, culture theory, philosophy, psychology, human-machine-interaction

Cultural techniques, societal norms and conventions regulate the social appropriateness of interventions in socially shared situations. For example, they determine the appropriate time for apologies, greetings, good wishes, reproaches or other social practices and rituals.

In a society where artificial agents such as personal assistants or domestic robots are very common, artificial and human actors have to show consideration for each other. Artificial agents have to learn culturally specific, socially appropriate manners, if we want to design them to be seen as decent.

In our project “poliTE – Social Appropriateness for Artificial Assistants”, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research in an effort to develop human-centered technology, we aim to understand the nature of decency between humans, before we evaluate to what extent designers of artificial assistants should try to implement features of social behaviour into their systems or to what extent they should try to make their products seem “polite”. For that purpose, we examine politeness, decorum, good manners and overall appropriate conduct linguistically, philosophically, psychologically and anthropologically to come to understand the genesis of decency, as well as quantifiable observables leading to the possibility of a social behaviour’s evaluation as proper or improper.

Our interdisciplinary approach fits well with your conference’s composition and we would like to share with fellow researchers and whomever is interested the results of our current research on the nature and genesis of decency, as well as our outlook on the need to implement social behaviours into technology.

Three Ways of Accounting for Evil

Zachary J. Goldberg

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich

Key Words:

Evil; Socratic; Wittgensteinian

My objective in this presentation is to describe and evaluate the different ways we can give an account of moral evil. There are three possibilities: First, one can reject the claim that the concept of evil is an appropriate subject of serious, secular, academic concern. The term “evil” can used to demonize one’s perceived enemies, it belongs perhaps only to fictional and religious contexts, and it can be used to distance ourselves from the target of our ascription and, subsequently, as a way to stop inquiry into their motivations and beliefs. These considerations are compelling, but ultimately unconvincing. When it comes to formulating positive accounts of evil there are two other methodologies we can employ: one is Socratic and the other Wittgensteinian. The Socratic approach advances the position that we can determine the necessary and sufficient conditions of all concepts. This approach has been fairly successful; we currently have several compelling definitions of evil in the philosophical literature. The disadvantage to this position is that conceptual pluralism possibly leads to conceptual vagueness. The Wittgensteinian approach insists that many or most concepts can be defined in terms of paradigms, and argues that a particular thing either is or is not a member of the class in question based on a “family resemblance”. The advantage of this approach is that rather than focusing on evil’s necessary and sufficient conditions, it allows us to turn our attention to evil’s significance in our lives. The occurrence of evil has critical implications for how we ought to think about ourselves and our interaction with others. The disadvantage is that without a prior and precise definition of evil, we may only recognize evil after it occurs. As a resolution, I recommend an ecumenical approach that preserves the advantages and eschews the disadvantages of each methodology.

Art, Evil and the Liberal Individual

John Tangney

University of Tyumen

Collective evil is often described with Hannah Arendt’s observations about its banality in mind, but personal evil can be cartoonish and highly distinctive. Archetypally evil figures from the theatre and cinema include Shakespeare’s Iago and Heath Ledger’s Joker. These fictional villains produce multiple explanations for why they do what they do, but the explanations overdetermine their motivations which therefore remain a mystery. James Hillman sees archetypally evil figures as daemonic geniuses who carry out their mission without regard for the norms that govern the lives of most individuals. This raises the question of the relationship between evil and artistic achievement, and therefore between evil and originality. Is the originality we prize in artists something that is easily mistaken for evil, or is it the real thing? To ask this question is to raise another question about the ontology of evil. Platonic and Augustinian thought equates evil with non-being. For their Catholic descendent, GK Chesterton’s Father Brown, evil is a reality but it is also the loss of reality.

Are the lies of the artist and those of the sociopath the same thing, as Socrates seems to think in the Republic? This paper will argue that, on the contrary, only the artist is fully capable of being a philosopher king in Plato’s terms. The execution of Socrates indicates that he was the only philosopher in the real Athens. The expulsion of artists from Plato’s ideal republic involves a recognition of the radical solitude of the philosopher-artist in worldly terms, as a necessary precondition of his ontological grounding in a moral order. What a polity made up of philosophers would look like is a question he and Augustine deferred and that Kant tried to answer with reference to a transcendental subject. The difference between evil and originality can therefore be seen with reference to the distinction between tyranny and monarchy, as well as between loneliness and solitude. The modern liberal individual is someone who vacillates between the two.

Indecency on Screen: Film Classification and the Censorship of Sex in Australia

Jade Jontef

La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

Key Words:

film classification, ratings, censorship, regulation, sex, sexuality, morality, indecency

The representation of sex in film has long concerned those responsible for regulating our screens. Often labelled obscene, offensive or indecent, films which explore sexuality in more explicit ways continue to face challenges when trying to secure classification or a suitable rating. In Australia, film classification is mandatory and government controlled. Three legislative documents govern the classification of films – The Classification (Publications, Films and Computer Games) Act 1995, the Guidelines for the Classification of Films and the National Classification Code. When making classification decisions, the Act requires the classification board and review board to take into account “the standards of morality, decency and propriety generally accepted by reasonable adults.” This requirement is reinforced by the Code which stipulates that film’s which “depict, express or otherwise deal with matters of sex . . . violence or revolting or abhorrent phenomena in such a way that they offend against the standards of morality, decency and propriety generally accepted by reasonable adults” should be refused classification. A film which is refused classification is effectively banned in Australia. While the classification boards are also required to take into account other matters, such as the artistic merit of a film, when making classification decisions, the supposed immorality or indecency of a film often overrides these considerations and ultimately determines whether a film is refused classification. This is particularly evident in cases where a film is said to contain offensive, gratuitous or socially unacceptable depictions of sex, sexual violence or fetishes. These sexually explicit images purported to offend against community standards of morality and decency are then prohibited, despite the first principle of the Code that “adults should be able to read, hear, see and play what they want.” In these cases, the decency or indecency of a film is used as justification to censor such material from adult audiences.

Evil Children in Latin American Film: A Tale of Dissent

Adriana Gordillo

Associate Professor, Minnesota State University, Mankato.

Key Words:

evil children, film, Latin America, heteronormativity, racism, social conflict, colonial past, economy, politics.

According to Karen Renner in Evil Children and the Popular Imagination, literary and cinematic works that explore infancy and evil have sprang since the middle of the 20th century. The essence of these visual narratives is that the evil child is the embodiment of rejected elements of society that possess kids and turn them into the evil that deranges the behavior of the ideal adult. These elements range from genetics to parenting, education to playtime, turning the symbolism of the evil child into a discussion about the politics of social normativity (Renner 7-8). Renner points out that “the majority of evil children characters are, by far, white, middle-to upper-class boys” followed by a distant second category of “white middle-to upper-middle-class girls, who in particular dominate the categories of the possessed child and changeling” (6). The exclusion of minority children is, in and on itself, a racist commentary. Minority children are, like their adult counterparts, assumed to be naturally evil (Renner 7).

Latin American filmography operates under the same parameters when it comes to the representation of evil children. It reflects a number of social issues that reflect the region’s racial divide and white/mixed privilege tradition as well as its heteronormative culture. Another use of the evil child deals with Latin America’s violent past, from a colonial to a recent past that reflects social disparities and political turmoil. In this presentation, I will explore the heternormative and racialized cultures of Latin America through the lenses of evil children portrayed in the movies El niño pez (2009), Hasta el viento tiene miedo (Mexico 2007), and Carne de tu carne (Colombia 1983). In these movies, evil children prompt the viewer to question sexual taboos and gender orientation while also exploring the political and socio-economical backdrop of the societies that they portray.

The Cordial Animal and the Brazilian Gothic: Evil Within, Monsters Without

CLAUDIO Vescia ZANINI

Professor of Literatures in English at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul

Key Words:

Brazilian cinema; horror cinema; The Cordial Animal; slasher film; representations of evil; monsters.

The growth of Brazilian horror cinema over the past decade is noteworthy, as attested by recent productions such as The Nightshifter (2018), Massacre County (2015), The Trace We Leave Behind (2017) The Night of the Chupacabras (2011), Mud Zombies (2008) and Good Manners (2017), movies that present monstrous characters, secluded properties or areas, the return of the past, and human and supernatural manifestations of evil. Variations of these horror tropes are also present in The Cordial Animal (2017), a slasher film directed by Gabriela Amaral Almeida whose plot revolves around a restaurant break-in and the ensuing tension shared by the burglars, the owner, staff members and customers, during which characters become both targets for evil deeds and perpetrators of evil. In this paper I discuss how The Cordial Animal approaches contemporary Brazilian manifestations of evil – notably through violence, social oppression against minorities and the exploitation of institutional and individual crises – and how the movie embeds these issues in the slasher movie conventions, which include graphic violence, an aura of mystery around the murderer, the violent destruction of the human body, and the construction of an oppressive atmosphere. Finally, I argue that The Cordial Animal is exemplary of Brazilian Gothic fiction, for it not only feeds on desires and quandaries of its context, but it also presents characters who fail to repress their evil instincts, thus becoming monsters. Texts on the slasher (Dika, 1987; Clover, 1992), the Gothic (Botting, 2004; Bruhm, 2007), and monster theory (Cohen, 1996; Asma, 2009) support the analysis.

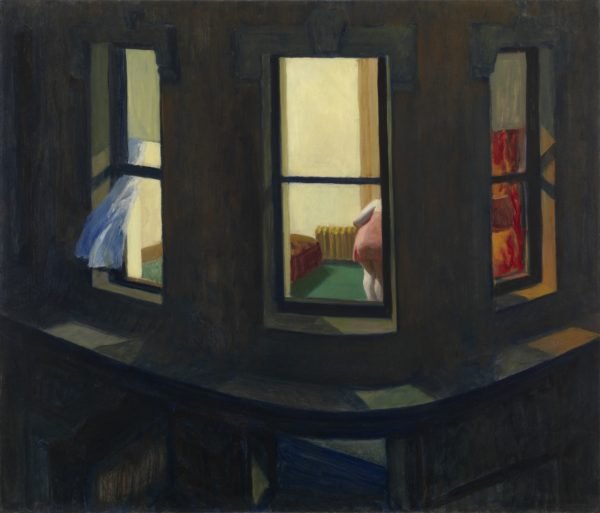

Painting the Creative Canvas of Evil

Rob Fisher

– No abstract available –